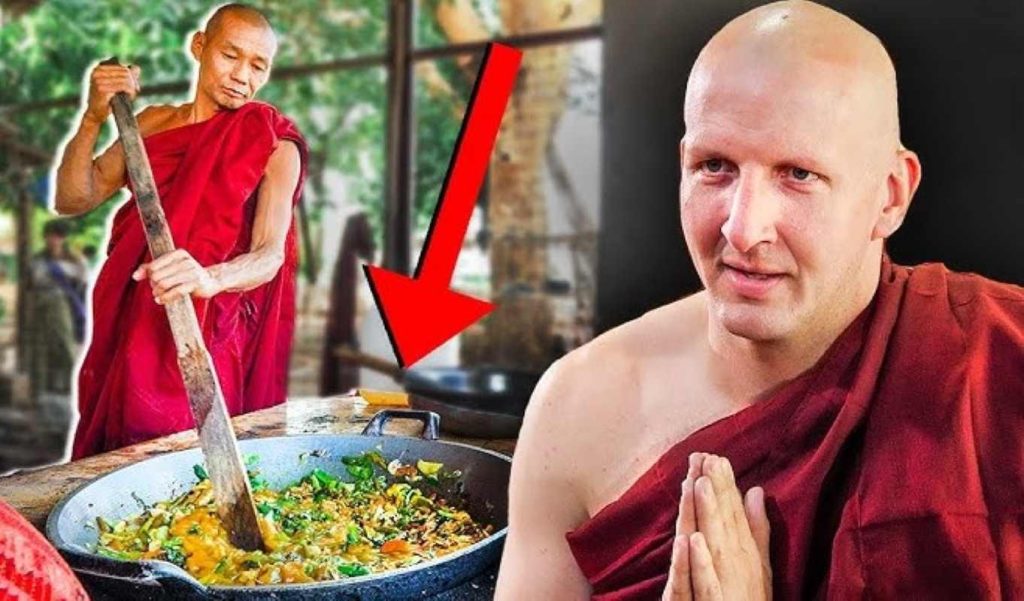

When modern people learn of the spiritual and religious undertone of monastic cooking traditions, they usually encounter surprises. Contemporary culinary practices and diets differ significantly from those found in the kitchens and dining halls of monasteries globally.

Monastic cooking reflects centuries-old practices of not just asceticism, but also culinary minimalism. However, these traditions have outlived several generations of monks and monastic sects, largely due to the values and sense of community they gender among adherents.

Monastic cooking traditions remain hidden in the annals of history. However, this piece will give new life to the customs, ingredients and philosophies behind monk food history.

The Philosophy Behind Monastic Cooking

Monks, across the ages, do not interact with food the same way average people do. Instead, these religious mystics regularly observe mindful eating rituals. While monks show deep gratitude for whatever food comes their way, self-grown or gifted, they also pay particular attention to its origin.

In the kitchen, monks are very intentional about what goes into the preparation of each meal. They never prepare food for profligacy; instead, excess resources are gifted to the needy. Another interesting monastic lifestyle is the practice of eating quietly and slowly. Records of monastic philosophies affirm that mindful eating rituals aid sensory awareness. By extension, monks teach themselves to enjoy whatever the monastery sets on their plates.

Monastic cooking traditions and dietary practices emphasize a philosophy that almost screams of listlessness or apathy. The average monk will gratefully thrive and survive on whatever grub they find available. It doesn’t matter if that is the first time they’re partaking in such a meal. However, where they have a benefit of choice, monks often tend toward vegetarianism and reduce dietary intake even in the face of excess.

Such a level of aloofness to food is possible because monks see the resource as one of the many tools that aid their journey to spiritual discipline. So, monastics never see food as an end in itself, nor do they abuse it. Instead, they use just enough to support the body while forging on to unify with divinity.

This brings the story of Brother Lawrence (Nicolas Herman) to mind. He was a Discalced Carmelite, a French monastic, from the 17th century. Herman lived the latter part of his life in a Catholic monastery, serving as the cook. According to a posthumous book that sets forth this monk’s teachings, it is possible to experience spiritual rhapsodies while washing pots and pans, and in the motions of meal preparation.

ALSO READ: DIY Pickling 101: The Science and Art Happening Inside the Jar

Regional Variations in Monastic Cooking Traditions

Religious food traditions have never been set in stone. Just as monastic sects often borrow dietary ethos from their underlying religions, local cultures equally influence what and how they eat. In this section, we’ll discuss some popular examples of how regional variations influence religious culinary traditions.

1. Buddhist Vegetarian Cuisines in East Asia

Monastery vegetarian recipes in East Asia are not a product of woke culture. Instead, they are grounded in the Buddhist philosophy of non-violence (ahimsa). It is based on this philosophy that monastics in the region avoid preparing meals with meat, fish, onions and garlic. “So, the practice of not eating onions and garlic is a form of non-violence?” someone is probably wondering. Well, in Jainism, also an East Asian religion, damaging the entire plant to harvest a root crop is seen as unsustainable. On the contrary, Buddhist monks simply stay away from onions and garlic to maintain purity.

Consequently, monastic cooking traditions in East Asia involve eating local staples like tofu and rice. A meat alternative, Seitan, is usually prepared by cooking wheat gluten. The monks in this region also make the most of whatever vegetables are in season. It is worth noting that allium-free diets are not peculiar to East Asian cultures. They are only an offshoot of Dharmic religious philosophies that are popular in the region.

2. Bread-and-Soup Traditions in European Monasteries

The monk diet history in Europe reveals a culinary trend that has outlived many generations: variants of bread-and-soup meals. While it is seldom spelt out explicitly, this meal pattern reflects the vegetarian and vegan leanings of monks around the world. The pottage and bread combination turned out to be good enough for monks to subsist upon, even during Lent.

The breads were often coarse and baked daily in the monastery. The soup, or pottage, was usually prepared using whatever grains, legumes, and vegetables that were in season. Most European monasteries maintained a garden, using some of the space to grow herbs for flavoring meals. During the Dark Ages, when it was easy to die from water-borne diseases, European monks took to brewing. During this period, monks became skilful brewers, producing beers that served as a safe alternative to water. To avoid wastefulness, some Italian monasteries were recorded as recycling stale bread by using it to prepare the Tuscan Bread Soup.

3. Middle Eastern Monasteries and Their Peculiar Diets

Middle Eastern monastic cooking traditions are also influenced by local cultures, as found in monasteries of other regions. However, some monastic sects in the Middle East are not overly strict with their stance on vegetarianism. While sects like the Orthodox Christians of Mount Athos enforce complete avoidance of animal products, wine and oil, some others are more consenting.

Monk food history in the Middle East reveals that these spirituals depend on staple grains (for bread, or gruel), and legumes as a protein source. It is common for Middle Eastern monasteries to have orchards and farms that are large enough to sustain the facility’s occupants. On some occasions, sick and convalescing individuals are allowed to eat animal products, olive oil and wine; during festivities too. However, all such dietary privileges are removed during communal fastings.

Rules, Rituals, and Monastery Food Culture

Some of the rules and rituals that govern monastic observance of fasts and feasts cut across multiple religions and sects. One of the common guidelines is to fast at set times, and to observe rules outlined in the doctrines of the monastic order concerned. Feast days are often chosen to coincide with either the commencement or culmination of a period of fasting.

For regular meals, monastic meals are usually prepared collectively; individualism is seldom permitted, even in hermit sects. Monks, particularly those from Greek, Korean and Japanese sects, are famed as the originators of the slow cooking culture. This culture entails taking time to mindfully prepare meals, bringing out the best flavors in the ingredients.

Dining is also almost always communal, with meals served in large halls at fixed times of the day. Even on feast days, debauchery and gluttony are hardly ever heard of, as such behaviors negate the ethos of monastic life. As part of their observance of gratitude, monks always say blessings before meals. It doesn’t matter if all they’re having is a small piece of bread and a watery bowl of lentil soup.

ALSO READ: The Bitter Truth: Inside the Dark Side of the Chocolate Supply Chain

Modern Influence and Preservation of Religious Food Traditions

Modern chefs and connoisseurs of contemporary recipes are borrowing cues from ancient monastic cooking traditions. If it’s not cooking technique, these foodies modify monastery vegetarian recipes, sometimes to tell stories with dishes as part of culinary tourism.

There are a handful of modern monastery cookbooks that describe dishes from the annals of ancient monks like Brother Lawrence. Such publications help immortalize the heritage of these age-long sects. In addition, the monastery cookbooks help unearth largely forgotten diets that could encourage healthy eating in a civilization grappling with obesity.

The lives of ancient monastics have influenced modern culinary culture than we know, or choose to admit. Who knows if the proponents of modern regenerative farming practices took their cue from records of monastic land cultivation? This is a plausible question because monks have always observed sustainable practices in the sourcing, preparation and cultivation of their food. In recent years, the slow cooking culture, a product of Carlo Petrini’s 20th-century Slow Food movement, is gaining popularity.

While everyone will agree to asceticism, there’s a lot we can learn from ancient monastic cooking traditions. The spirituality, sustainable interaction with nature, and allowing these values to influence how we cook and eat. Consider adopting some monastic principles, like dietary mindfulness and simplicity, in your kitchen and dining room.

In the monastery kitchen, every meal is a meditation, and every ingredient is a gift.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Babatunde Olufemi is a food scientist, educator, and science-based food writer with academic and practical exposure to food processing, nutrition, food safety, and the global food industry. Through Quill of Grubs, he breaks down complex food science topics into clear, accessible explanations for everyday readers, students, and professionals.