Scan an average grocery store aisle, and you are likely to encounter several acclaimed ‘high-protein foods.’ Cookies, cereals, energy bars, name it, now have some form of protein claim on their labels. This new trend raises questions about the reliability of protein content claims on food labels.

Consumers who gravitate towards protein claims on food labels are often looking to improve muscle mass, satiety, or overall health. However, from the few lines you have read so far, it’s probably becoming obvious that there may be more to protein marketing than meets the eye. How can the average food consumer interpret the meaning of a high-protein label, and is it even subject to regulation?

These and more are some of the questions that this piece will address. Protein labeling science will help readers distinguish between protein quantity and quality. You’ll also get to dispel a couple of protein marketing myths while improving your food label literacy. Nothing beats getting the appropriate nutritional value from food products that you expect to boost your health.

What Does ‘High-Protein’ Actually Mean on a Label?

What qualifies, legally, as high-protein foods is often a function of where you reside.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom and the European Union, you can only label food products as ‘high protein’ if 20% or more of their total energy comes from protein. So, in this region, protein labeling is a function of the nutrient’s caloric contribution per serving.

United States

Meanwhile, the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only allows the labeling of products containing a minimum of 20% Daily Value (DV) of protein per serving as ‘high protein.’ Let’s break that down. Based on a 2000-calorie daily diet, an average for adults and children of three years and above, the FDA’s standard DV for protein is 50g. Simply put, local regulators recommend that Americans consume a minimum of 50g of protein per day. So, before any food product can tout itself as ‘high-protein,’ a single serving of that product must contain at least 20% (10g) of the consumer’s daily protein requirement.

Canada

Canada follows a similar standard to the US, but strictly regulates ‘High Quality Protein’ claims. The goal is to protect consumers from label-related misinformation.

The serving size of acclaimed high-protein foods may, however, mislead consumers. For instance, some manufacturers may declare the protein percentage of a small and inconsequential serving size of their product. Meanwhile, when scaled up to the nutrient density per 100g of the product, the protein content may not even meet the daily value requirement.

To sidestep the serving size trick of misrepresenting food’s protein content, it is essential to understand the difference between absolute and relative protein. Food labels that sport absolute protein content declare the total mass (in grams) of protein in that particular serving. Meanwhile, labels with relative protein content declare protein percentage as a function of total calories supplied by a specific serving.

ALSO READ: From Natural Pigments to Edible Dyes: The Science Coloring Our Food

Protein Quantity vs Protein Quality

Another box you need to tick in your effort to understand protein labeling science is protein quality. Why? It is possible that a food product has a high protein percentage and contributes little to your nutritional health. Think of it like AI-generated content that is bulky, but full of fluff.

The building blocks of proteins, amino acids, can be categorized as essential or non-essential. Food experts suggest that products containing a higher proportion of essential amino acids are more nutritionally beneficial. This preference for essential amino acids is because the human body can only get them from dietary sources. In contrast, the body can synthesize the 11 non-essential amino acids internally.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, nine of the 20 amino acids that humans need for metabolism are essential. So, when a food product contains all nine essentials, it qualifies as a source of complete protein. Conversely, products lacking, or low in, one or more amino acids are said to be a source of incomplete protein.

According to the FDA’s dietary protein quality evaluation guide, absorption and digestibility influence protein quality scoring. Bioavailability is the ability of the digestive system to digest, absorb, and utilize food nutrients with ease. Adding iron shavings from a lathe machine to food does not make it rich in that mineral. Metallic iron, in that form, is not bioavailable. Meanwhile, the body can easily digest and utilize iron molecules existing as part of organic compounds, like the ‘heme’ complex of blood.

How Protein Claims Can Be Misleading

Profit-centric manufacturers may use macronutrient labeling to greenwash their products. Consider products that indeed qualify, by regulatory standards, as high-protein foods, but contain constituents that render them unhealthy. Such scenarios make the discussion about macronutrient labeling and its link to healthy diets a convoluted one. For instance, a product may be inordinately high in fat or sugar and still use the high-protein claim. This is not hypothetical; many Big Food brands are rolling out protein-based drinks and snacks.

Not all ‘high-protein foods are inherently rich in the said macronutrient. Some products in this category simply had protein isolates added in during production.

In a previous post, we made a case for the health implications of consuming ultra-processed foods. Judging by all the legal guardrails set for commercial high-protein foods, even ultra-processed ones can make the cut.

Animal vs Plant Protein: What Labels Don’t Tell You

What most food labels won’t tell you, beyond nutrient density, is the profile of macronutrients in the product. For instance, food labels seldom state the amino acids that make up their protein claims. So, it may be difficult to tell if the proteins the product supplies are ‘complete,’ or ‘incomplete.’

According to a 2021 review study by a team of Singaporean food scientists, protein from animal sources is better for building lean mass. This probably explains why many bodybuilders favor animal-based proteins. However, Healthline takes a more nuanced stance in comparing protein from animal and plant sources.

Nutritionists suggest that animal proteins are a more likely source of complete protein. However, it’s possible to make up for deficiencies of specific amino acids in staple crops, like wheat, by combining them with other crops during meal preparation.

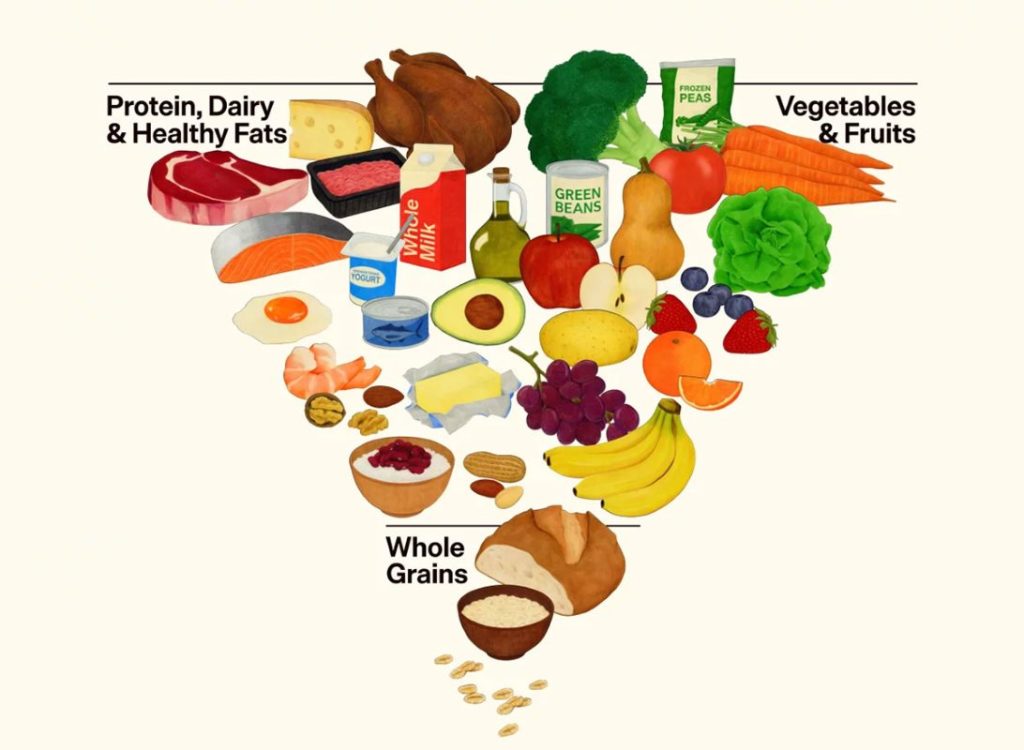

Another established merit of animal protein is its bioavailability, meaning it is digested easily relative to most plant proteins. However, a major drawback of animal protein sources is their fatty accompaniment, which is often linked to cardiovascular diseases. In contrast, plant proteins offer lower caloric contributions to the diet.

Before bringing this section to a climax, it is necessary to state that neither animal nor plant protein is superior. Instead of following diet-tribes and dogmatic food narratives, it is better to demystify and understand the quality profile of whatever is on the table. Don’t demonize a hearty plate of BBQ steak, or a yummy bowl of lentils.

Does High-Protein Automatically Mean Healthier?

The question of whether ingesting high-protein foods translates to healthy eating was addressed earlier. However, it requires a little more emphasis for those who missed it.

For one, protein-based diets can help with weight regulation. Like carbohydrates, protein supplies 4 kcal/g, but keeps you fuller for longer. Compared to fats that supply 9 kcal/g, protein has a lower caloric density and can put the brakes on weight gain while still helping you to feel satisfied.

Beyond satiety and nutrient density, how the protein-rich food is processed matters. Of course, eating raw mutton or uncooked beans is not advisable. Nonetheless, minimal processing helps preserve the integrity and quality of protein in fresh foods. Summarily, ultra-processing protein-heavy foods can make them unhealthy.

If you’re looking to manage your weight, say add on lean muscle; recover after a medical relapse; an athlete whose routines involve endurance training, then consuming higher-than-average quantities of protein could be helpful. However, people who are solely reliant on dietary supplements, have diagnosed kidney conditions, or lead sedentary lives, should avoid excessive consumption of proteins.

How to Read Protein Claims Like a Food Scientist

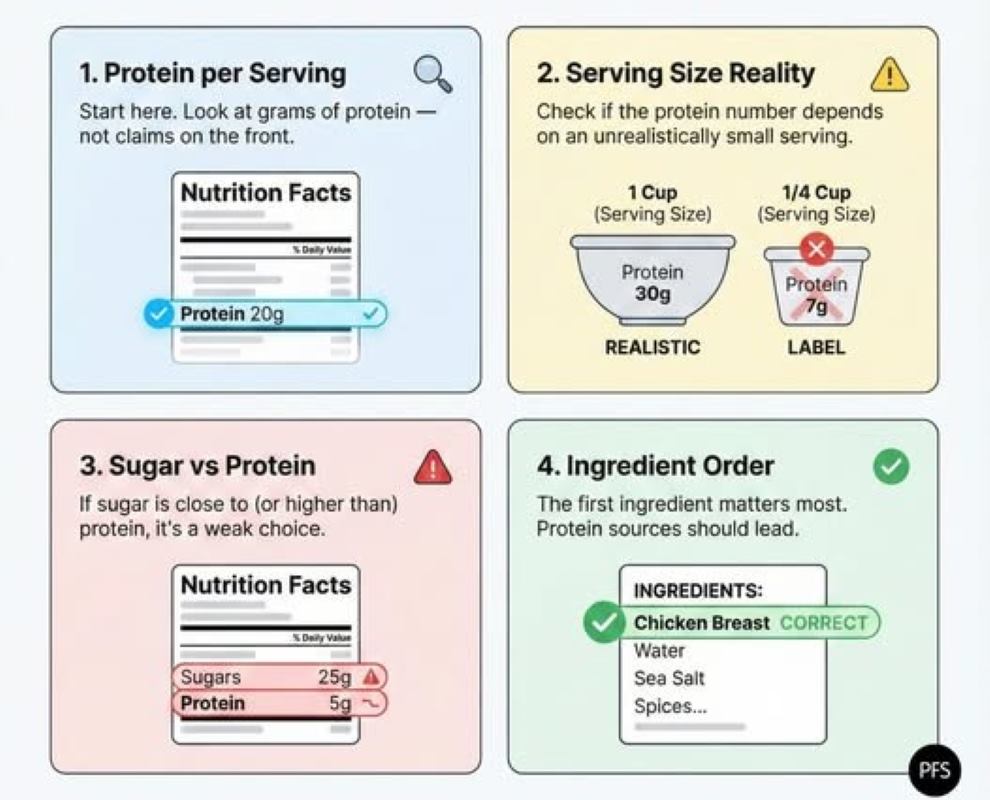

Unbundling protein marketing myths is not as difficult as it seems. First off, make efforts to understand your daily protein requirements. This will help you choose appropriate high-protein foods and know the right quantity to eat per serving.

Here are some practical steps to help you make the right high-protein food purchase:

- Check grams of protein per serving, and per 100g of the product.

- Compare the product’s calories to protein ratio.

- Look at the ingredient list; an excessively long list likely infers the product is ultra-processed.

- See if you can identify the product’s protein source.

ALSO READ: Els Enfarinats: The Spanish Festival Where Flour, Eggs, and Power Are Thrown Into Chaos

Why Protein Marketing Is Exploding

Food manufacturers often launch new products to satisfy or fill a demand gap. Sometimes, protein-rich products are developed in response to ebbing trends in wellness circles. So, it is little surprise that food brands are keying in on the wellness market.

On the consumer side, carbs have become demonized in mainstream media, making them embrace protein claims. Also, wellness trainers and fitness experts are glorifying protein-based diets as best for folks looking to shed weight. Finally, more people are looking to get ripped, causing the fitness culture to birth a billion-dollar industry.

Closing Remarks

‘High-protein’ is a regulated food claim, but it is very easy for consumers to misunderstand. This is why a little dose of food label literacy helps some. The nutrient claims explained in this piece help readers realize that quality, context, and processing matter in how consumers assess proteins.